Voyager 2

- För andra betydelser, se Voyager.

Voyager 2 | |

| Status | aktiv |

|---|---|

| Typ | Förbiflygare |

| Program | Voyagerprogrammet |

| Organisation | NASA |

| NSSDC-ID | 1977-076A[1] |

| Webbplats | http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov |

| Uppskjutning | |

| Uppskjutningsplats | Cape Canaveral LC-41 |

| Uppskjutning | 20 augusti 1977, 14:29:00 UTC (för 47 år och 141 dagar sedan) |

| Uppskjutningsfarkost | Titan III-E Centaur |

| Förbiflygning av Jupiter | |

| Datum | 9 juli 1979, 22:29 UTC |

| Minsta avstånd | 570 000 km |

| Förbiflygning av Saturnus | |

| Datum | 25 augusti 1981, 03:24:05 UTC |

| Minsta avstånd | 101 000 km |

| Förbiflygning av Uranus | |

| Datum | 24 januari 1986, 17:59:47 UTC |

| Minsta avstånd | 81 500 km |

| Förbiflygning av Neptunus | |

| Datum | 25 augusti 1989, 03:56:36 UTC |

| Minsta avstånd | 4 951 km |

| Egenskaper | |

| Massa | 721,9 kg |

| Effekt | 420 W |

Voyager 2 är en obemannad rymdsond inom Voyagerprogrammet som skickades upp i rymden av Nasa 20 augusti 1977, med en Titan 3E Centaur. Farkosten har samma konstruktion som Voyager 1. Båda farkosterna sändes ut för att undersöka planeter i solsystemet och sände tillbaka bilder och mätdata som helt har förändrat synen på jordens grannplaneter.

På grund av ett uppskjutningsfel med Voyager 1 glömde man bort att sända en kod till Voyager 2 vilket gjorde att huvudantennen inte fungerade. Man bytte då till reservantennen men det visade sig vara ett inbyggt fel i reservantennen vilket resulterade i ett mycket litet informationsband. För att lösa problemet fick Nasas ingenjörer ställa in mottagarna mycket precist för att få rätt frekvensomfång.

Efter att ha passerat Jupiter och Saturnus samt några av deras större månar blev Voyager 2 den första farkosten som passerat över Uranus och Neptunus. Detta var möjligt tack vare att planeterna låg placerade på ett mycket gynnsamt sätt, något som återkommer vart 175:e år.

Last

Förutom vetenskapliga instrument har Voyagersonderna utrustats med varsin grammofonskiva: Voyager Golden Record.

Avståndet Voyager 2 befinner sig på

I oktober 2024 befann sig Voyager 2 på ett avstånd av ungefär 20,6 miljarder kilometer från solen, eller cirka 137,7 astronomiska enheter – ett avstånd som ökar med ungefär tre enheter per år.[2]

Sonden beräknas fortsätta sända data till jorden fram till 2020-talet, tills batterierna tar slut och signalerna blir alltför svaga för att kunna tydas. Fördröjningen för en signal att nå fram ökar med cirka 30 minuter för varje år som går. Trots detta enorma avstånd är det inte det längsta ett människoskapat objekt har tagit sig från jorden. Rekordet hålls av Voyager 1, som befinner sig ungefär tre miljarder kilometer före Voyager 2.

NASA meddelade den 11 december 2018 att sonden den 5 november samma år blev det andra artificiella objektet i världshistorien som flög ut i den interstellära rymden.[3][4]

Se även

Källor

Fotnoter

- ^ ”NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive” (på engelska). NASA. https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1967-008A. Läst 27 mars 2020.

- ^ ”Where are the Voyagers?” (på engelska). Voyager - The Interstellar Mission. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/where/. Läst 2 november 2015.

- ^ Andersson, Jennifer (12 december 2018). ”Voyager 2 intar rymden mellan stjärnorna”. Populär Astronomi. https://www.popularastronomi.se/2018/12/voyager-2-intar-rymden-mellan-stjarnorna/. Läst 12 december 2018.

- ^ ”NASA’s Voyager 2 Probe Enters Interstellar Space” (på engelska). NASA. 11 december 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-s-voyager-2-probe-enters-interstellar-space. Läst 12 december 2018.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Media som används på denna webbplats

This image shows the locations of Voyagers 1 and 2. Voyager 1 is traveling a lot and has crossed into the heliosheath, the region where interstellar gas and solar wind start to mix.

Suggested for English Wikipedia:alternative text for images: orange area at left labeled Bow Shock appears to compress a pale blue oval-shaped region labeled Heliosphere extending to the right with its border labeled Heliopause. A central dark blue circular region is labeled Termination Shock with the gap between it and the Heliosphere labeled Heliosheath. Centred in the blue region is a concentric set of ellipses around a bright spot with two white lines curving away from it: the upper line labeled Voyager 1 ends outside the dark blue circle; the lower line labeled Voyager 2 appears inside.

Remark: This picture is from 2005. Today (3 October 2018) Voyager 1 is well beyond the Heliopause and Voyager 2 is about to cross the Heliopause soon (see the latest "3 October 2018" image).[1] Further, there has been evidence that the Bow Shock does not exist; whether the Heliosheath has this long of a tail is doubtful, too. It might be almost spherical.NASA photograph of one of the two identical Voyager space probes Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched in 1977.

The 3.7 metre diameter high-gain antenna (HGA) is attached to the hollow ten-sided polygonal body housing the electronics, here seen in profile. The Voyager Golden Record is attached to one of the bus sides.

The angled square panel below is the optical calibration target and excess heat radiator.

The three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) are mounted end-to-end on the left-extending boom. One of the two planetary radio and plasma wave antenna extends diagonally left and down, the other extends to the rear, mostly hidden here. The compact structure between the RTGs and the HGA are the high-field and low-field magnetometers (MAG) in their stowed state; after launch an Astromast boom extended to 13 metres to distance the low-field magnetometers.

The instrument boom extending to the right holds, from left to right: the cosmic ray subsystem (CRS) above and Low-Energy Charged Particle (LECP) detector below; the Plasma Spectrometer (PLS) above; and the scan platform that rotates about a vertical axis.

The scan platform comprises: the Infrared Interferometer Spectrometer (IRIS) (largest camera at right); the Ultraviolet Spectrometer (UVS) to the right of the UVS; the two Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) vidicon cameras to the left of the UVS; and the Photopolarimeter System (PPS) barely visible under the ISS.

Suggested for English Wikipedia:alternative text for images: A space probe with squat cylindrical body topped by a large parabolic radio antenna dish pointing upwards, a three-element radioisotope thermoelectric generator on a boom extending left, and scientific instruments on a boom extending right. A golden disk is fixed to the body.NASA's Voyager 1 took this photograph of Saturn on Oct. 18, 1980, 34 million kilometers (21.1 million miles) from the planet. The photograph was taken on the last day that Saturn and its rings could be captured within a single narrow-angle camera frame as the spacecraft closed in on the planet for its nearest approach on Nov. 12. Dione, one of Saturn's inner satellites, appears as three color spots just below the planet's south pole. An abundance of previously unseen detail is apparent in the rings. For example, a gap in the dark, innermost ring, called the C-ring or crepe ring, is clearly shown. Material is seen within the relatively wide Cassini Division, separating the middle, B-ring from the outermost ring, the A-ring. The Encke Division is shown near the outer edge of the A-ring. The detail in the rings' shadows cast on the planet is of particular interest: the broad, dark band near the equator is the shadow of the B-ring; the thinner, brighter line is just to the south of the shadow of the less dense A-ring.

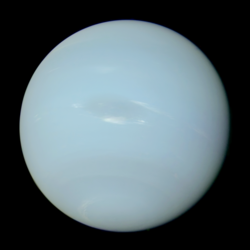

Författare/Upphovsman: NASA / Voyager 2 / PDS / OPUS / Ardenau4, Licens: CC0

Neptune on 1989-08-17, taken by NASA's Voyager 2 probe. This color image was composed of three frames, orange, green, and blue, taken by Voyager 2's imaging system. This color image has been calibrated to best represent Neptune's true color and appearance. Based on: Irwin, Patrick G J (2023-12-23). "Modelling the seasonal cycle of Uranus’s colour and magnitude, and comparison with Neptune". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 527 (4): 11521–11538. DOI:10.1093/mnras/stad3761. ISSN 0035-8711.

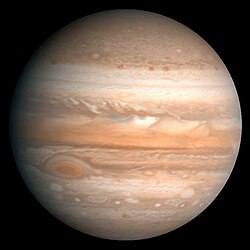

Original Caption Released with Image: This processed color image of Jupiter was produced in 1990 by the U.S. Geological Survey from a Voyager 2 image captured in 1979. The colors have been enhanced to bring out detail. Zones of light-colored, ascending clouds alternate with bands of dark, descending clouds. The clouds travel around the planet in alternating eastward and westward belts at speeds of up to 540 kilometers per hour. Tremendous storms as big as Earthly continents surge around the planet. The Great Red Spot (oval shape toward the lower-left) is an enormous anticyclonic storm that drifts along its belt, eventually circling the entire planet.

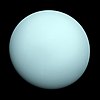

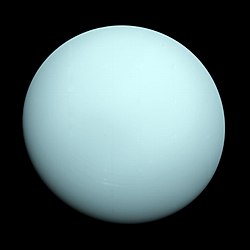

This is an image of the planet Uranus taken by the spacecraft Voyager 2 in 1986. See Uranus.jpg for how Uranus would appear in visible light.

PIA22921: Voyager 2 and the Scale of the Solar System (Artist Concept)

https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22921

This artist's concept puts solar system distances -- and the travels of NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft -- in perspective. The scale bar is in astronomical units, with each set distance beyond 1 AU representing 10 times the previous distance. One AU is the distance from the Sun to Earth, which is about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers. Neptune, the most distant planet from the Sun, is about 30 AU.

Much of the solar system is actually in interstellar space. Informally, the term "solar system" is often used to mean the space out to the last planet. Scientific consensus, however, says the solar system goes out to the Oort Cloud, the source of the comets that swing by our sun on long time scales. Beyond the outer edge of the Oort Cloud, the gravity of other stars begins to dominate that of the Sun.

The inner edge of the main part of the Oort Cloud could be as close as 1,000 AU from our Sun. The outer edge is estimated to be around 100,000 AU.

Voyager 2, the second farthest human-made object after Voyager 1, is around 119 AU from the Sun. Indications from the scientific instruments suggest Voyager 2 passed beyond our heliosphere (the bubble of plasma the Sun blows around itself) and into interstellar space (the space between stars) in November 2018. The heliosphere has a turbulent outer boundary known as the heliosheath. The termination shock is the inner boundary of the heliosheath and the heliopause is the outer boundary, beyond which lies interstellar space. Voyager 2 crossed the termination shock at 84 AU in August 2007.

It will take about 300 years for Voyager 2 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly about 30,000 years to fly beyond it.

Voyager 2 is heading away from the Sun about 36 degrees out of the ecliptic plane (plane of the planets) to the south, toward the constellations of Sagittarius and Pavo. In about 40,000 years, Voyager 2 will be closer to another star than our own Sun, coming within about 1.7 light years of a star called Ross 248, a small star in the constellation of Andromeda.

The Voyager spacecraft were built by JPL, which continues to operate both. JPL is a division of Caltech in Pasadena. California. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit https://www.nasa.gov/voyager and https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov.