Vetenskapsåret 1789

| Vetenskapsåret 1789 | |

| 1788 · 1789 · 1790 | |

| Humaniora och kultur | |

|---|---|

| Konst, litteratur, musik och teater | |

| Samhällsvetenskap och samhälle | |

| Krig | |

| Teknik och vetenskap | |

| Vetenskap |

Händelser

- 10 juli - Alexander Mackenzie utforskar Mackenzieflodens delta.

- Antoine de Jussieu publicerar sin bok Genera Plantarum.

- Martin Heinrich Klaproth upptäcker grundämnena zirkonium och uran.

- Antoine Lavoisier publicerar sin bok Traité élémentaire de chimie, ansedd att vara den första moderna kemiboken, där han formulerar lagen om massans bevarande och förnekar existensen av flogiston.

- Gilbert White publicerar The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne.

Anatomi

- Okänt datum - Antonio Scarpa publicerar Anatomicæ disquisitiones de auditu et olfactu, en klassisk avhandling om hörsel och luktorgan.[1]

Botanik

- Okänt datum - Antoine Laurent de Jussieu publicerar Genera Plantarum: secundum ordines naturales disposita, juxta methodum in Horto regio parisiensi exaratam, anno M.DCC.LXXIV, som länge blir en grund för klassificeringssystemet för gömfröväxter.[2]

Pristagare

- Copleymedaljen: William Morgan, walesisk läkare.

Födda

- 7 februari - Joakim Frederik Schouw (död 1852), dansk naturforskare.

- 16 mars - Georg Ohm (död 1854), tysk fysiker.

- 26 mars - William Charles Redfield (död 1857), amerikansk meteorolog.

- 21 augusti - Augustin Louis Cauchy (död 1857), fransk matematiker.

- 9 september - William Cranch Bond (död 1859), amerikansk astronom.

- 28 september - Richard Bright (död 1858), brittisk läkare.

- 25 oktober - Heinrich Schwabe (död 1875), tysk astronom.

- 1 november - Johan Emanuel Wikström (död 1856), svensk botaniker.

Avlidna

- 25 maj - Anders Dahl (född 1751), svensk botaniker, Linné-lärjunge.

- 23 november - Anders Hellant (född 1717), svensk astronom.

Källor

Fotnoter

- ^ Richardson, Benjamin Ward (18 augusti 1886). ”Antonio Scarpa, F.R.S., and Surgical Anatomy”. The Asclepiad (London: Longmans, Green and Co.) "4" (16): ss. 128–157. https://books.google.com/?id=-xVCQGjm3ZEC. Läst 10 juni 2008.

- ^ ”De Jussieu”. Arkiverad från originalet den 5 juni 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130605123728/http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/De_Jussieu.

Media som används på denna webbplats

(c) Boston på engelska Wikipedia & John Stephen Dwyer, CC BY-SA 3.0

Statue personifying "Science" in front of the Boston Public Library on Copley Square of the Back Bay of Boston. January 2009 photo by John Stephen Dwyer

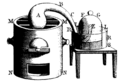

Hand sketch engraving made by madamme Lavoisier in the 18th century featured in "Traité élémentaire de chimie" retrieved from http://mattson.creighton.edu/History_Gas_Chemistry/Lavoisier.html Lavoisier performed his classic twelve-day experiment in 1779 which has become famous in history. First, Lavoisier heated pure mercury in a swan-necked retort over a charcoal furnace for twelve days. A red oxide of mercury was formed on the surface of the mercury in the retort. When no more red powder was formed, Lavoisier noticed that about one-fifth of the air had been used up and that the remaining gas did not support life or burning. Lavoisier called this latter gas azote. (Greek 'a' and ' zoe' = without life). He removed the red oxide of mercury carefully and heated it in a similar retort. He obtained exactly the same volume of gas as disappeared in the last experiment. He found that the gas caused flames to burn brilliantly, and small animals were active in it as Joseph Priestley had noticed in his experiment. Finally, on mixing the two types of gas, i.e. the gas left in the first experiment, and that given out in the second experiment, he got a mixture similar to air in all respects. In his experiments Lavoisier analysed air into two constituents: the one which supports life and combustion, and is one-fifth by volume of air he called oxygen (Greek, oxus=acid, gen=beget), the other four-fifths which does not he called azote. This latter gas is now called nitrogen. From the two gases he synthesised something that has the characteristics of air.