Månens baksida

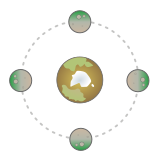

Månens baksida är det halvklot av månen som alltid vänder sig bort från jorden. Detta beror på att månen roterar runt sin egen axel med samma hastighet som den kretsar runt jorden.

Beskrivning

Baksidan består av oländig terräng med en stor mängd nedslagskratrar och ett fåtal månhav. Här finns en av solsystemets största kratrar Sydpol-Aitkenbassängen. Månens båda sidor upplever två veckor av solljus följt av två veckors natt. Bortre sidan kallas ibland "månens mörka sida", vilket snarare syftar på osynlig än brist på ljus.[1][2][3][4]

Omkring 18 procent av den bortre sidan är ibland synlig från jorden på grund av libration. Återstående 82 procent har förblivit oobserverad fram till år 1959, då baksidan fotograferades av sovjetiska rymdsonden Luna 3. År 1960 publicerade Sovjetunionens Vetenskapsakademi den första atlasen över månens baksida. Astronauterna på Apollo 8 var de första människorna som såg baksidan med blotta ögat när de var i omloppsbana runt månen 1968. Alla bemannade och obemannade mjuklandningar hade gjorts på månens framsida, men 3 januari 2019 genomförde den kinesiska rymdfarkosten Chang'e 4 den första landningen på månens baksida.[5]

Astronomer har föreslagit att man skulle bygga ett stort radioteleskop på baksidan, där månen skulle vara ett skydd mot möjliga radiostörningar från jorden.[6]

Se även

Bildgalleri

- Sovjetiskt frimärke från 1959.

- På grund av bunden rotation döljs månens baksida

- Bild från Luna 3 som för första gången visar månens baksida

Referenser

- Den här artikeln är helt eller delvis baserad på material från engelskspråkiga Wikipedia, Far side of the Moon, 23 april 2019.

Noter

- ^ Sigurdsson, Steinn (9 juni 2014). ”The Dark Side of the Moon: a Short History”. http://scienceblogs.com/catdynamics/2014/06/09/the-dark-side-of-the-moon-a-short-history/. Läst 23 april 2019.

- ^ O'Conner, Patricia T.; Kellerman, Stewart (6 september 2011). ”The Dark Side of the Moon”. https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2011/09/dark-side-of-the-moon.html. Läst 23 april 2019.

- ^ Messer, A'ndrea Elyse (9 juni 2014). ”55-year-old dark side of the moon mystery solved”. Penn State News. http://news.psu.edu/story/317841/2014/06/09/research/55-year-old-dark-side-moon-mystery-solved. Läst 23 april 2019.

- ^ Falin, Lee (5 januari 2015). ”What's on the Dark Side of the Moon?”. Arkiverad från originalet den 30 november 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20181130124604/http://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/science/what%E2%80%99s-on-the-dark-side-of-the-moon. Läst 23 april 2019.

- ^ ”Chinese spacecraft makes first landing on moon's far side”. AP NEWS. 3 januari 2019. https://apnews.com/c4dc6858a32b4b61bdbc6aebf5459a91. Läst 3 januari 2019.

- ^ Kenneth Silber. ”Down to Earth: The Apollo Moon Missions That Never Were”. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/canceled-apollo-missions.

Externa länkar

- Lunar and Planetary Institute: Exploring the Moon

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Månens baksida.

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Månens baksida.

Media som används på denna webbplats

Historic photo - the first full view of significant quality (cropped frame number 29)[1], of the first series of photos of the far side of the Moon, taken by Luna 3, October 7, 1959. The dark patches at left include Mare Crisium (on the near side), Mare Smythii, and Mare Marginis (on the border of the near and far sides). At bottom is Mare Australe. The dark patch above right of center is Mare Moscoviense, and below right of center is Tsiolkovskiy crater. Below and to the right of Tsiolkovskiy is Jules Verne crater.

Författare/Upphovsman: Smurrayinchester, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

A illustration demonstrating simple synchronous rotation. As the moon takes exactly one orbit to rotate one about its axis, the inhabitants of the planet will never be able to see the green side of the moon.

1959 Soviet Union 40 kopeks stamp. Photo of invisible side of Moon.

(c) Gregory H. Revera, CC BY-SA 3.0

Full Moon photograph taken 10-22-2010 from Madison, Alabama, USA. Photographed with a Celestron 9.25 Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope. Acquired with a Canon EOS Rebel T1i (EOS 500D), 20 images stacked to reduce noise. 200 ISO 1/640 sec.

Far side of the moon, by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Orthographic projection centred at 180° longitude, 0° latitude.

Because the moon is tidally locked (meaning the same side always faces Earth), it was not until 1959 that the farside was first imaged by the Soviet Luna 3 spacecraft (hence the Russian names for prominent farside features, such as Mare Moscoviense). And what a surprise – unlike the widespread maria on the nearside, basaltic volcanism was restricted to a relatively few, smaller regions on the farside, and the battered highlands crust dominated. A different world from what we saw from Earth.

Of course, the cause of the farside/nearside asymmetry is an interesting scientific question. Past studies have shown that the crust on the farside is thicker, likely making it more difficult for magmas to erupt on the surface, limiting the amount of farside mare basalts. Why is the farside crust thicker? That is still up for debate, and in fact several presentations at this week's Lunar and Planetary Science Conference attempt to answer this question.

The Clementine mission obtained beautiful mosaics with the sun high in the sky (low phase angles), but did not have the opportunity to observe the farside at sun angles favorable for seeing surface topography. This WAC mosaic provides the most complete look at the morphology of the farside to date and will provide a valuable resource for the scientific community. And it's simply a spectacular sight!

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) Wide Angle Camera (WAC) is a push-frame camera that captures seven color bands (321, 360, 415, 566, 604, 643, and 689 nm) with a 57 km swath (105 km swath in monochrome mode) from a 50 km orbit. One of the primary objectives of LROC is to provide a global 100 m/px monochrome (643 nm) base map with incidence angles between 55° and 70° at the equator, lighting that is favorable for morphological interpretations. Each month, the WAC provides nearly complete coverage of the Moon under unique lighting. As an added bonus, the orbit-to-orbit image overlap provides stereo coverage. Reducing all these stereo images into a global topographic map is a big job, which is being led by LROC Team Members from the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR). Several preliminary WAC topographic products have appeared in LROC featured images over the past year (Orientale basin, Sinus Iridum). The WAC topographic dataset will be completed and released later this year.

The global mosaic released today is comprised of over 15,000 WAC images acquired between November 2009 and February 2011. The non-polar images were map-projected onto the GLD100 shape model (WAC derived 100 m/px DTM), while polar images were map-projected on the LOLA shape model. In addition, the LOLA-derived crossover-corrected ephemeris and an improved camera pointing provide accurate positioning (better than 100 m) of each WAC image.This animation features satellite images of the far side of the Moon, illuminated by the Sun, as it crosses between the DSCOVR spacecraft's Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) and telescope, and the Earth — one million miles (1.6 million km) away. The times of the images span from 3:50 p.m. to 8:45 p.m. EDT on July 16, 2015. The time of the New Moon was at 9:26 p.m. EDT on July 15.