Jupiters naturliga satelliter

Jupiter har 95 bekräftade månar (juli 2024).[1][2]

Månar

Inre månar

De fyra största månarna (Io, Europa, Ganymedes och Callisto) upptäcktes 1610 av Galileo Galilei och kallas de galileiska månarna. Innanför dessa finns fyra små månar (Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea och Thebe) med diametrar mellan 20 och 200 km. Tillsammans kallas dessa åtta månar de reguljära månarna och förefaller vara uppbyggda av samma material, samma blandning is och sten, som kanske utgör Jupiters inre.[3] Dessa månar bildades förmodligen av materia som blev över när Jupiter bildades. De galileiska månarna växte sig stora eftersom de bildades där stoftet och isen var som tätast.[4]

Yttre månar

De yttre månarna är omkring nittio små månar med en diameter på 1–160 km. De flesta av de yttre månarna anses vara infångade asteroider från asteroidbältet. Den största av de yttre månarna är Himalia. Den är 170 km i diameter och ligger 11 461 000 km från Jupiter och tar 250,56 dygn på sig att kretsa ett varv kring Jupiter.[5]

Tabell över Jupiters kända månar

Tabellen listar Jupiters alla bekräftade naturliga satelliter i stigande ordning efter banradien. Satelliter utan nummer är sådana som ännu inte fått ett officiellt namn av Internationella astronomiska unionen.

| Färgförklaring | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inre Månar | Galileiska månar | Themisto | Himalia-gruppen | Carpo-gruppen | Valetudo | Ananke-gruppen | Carme-gruppen | Pasiphae-gruppen |

| Nr. | Namn | Banans halva storaxel (km)[1] | Skenbar magnitud (mag)[1] | Diameter (km)[1] | Omloppstid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XVI | Metis | 128 000 | 17,5 | 44 | 0,30 |

| XV | Adrastea | 129 000 | 18,7 | 16 | 0,30 |

| V | Amalthea | 181 400 | 14,1 | 168 | 0,50 |

| XIV | Thebe | 221 900 | 16,0 | 98 | 0,68 |

| I | Io | 421 800 | 5,0 | 3 643 | 1,77 |

| II | Europa | 671 100 | 5,3 | 3 122 | 3,55 |

| III | Ganymedes | 1 070 400 | 4,6 | 5 262 | 7,16 |

| IV | Callisto | 1 882 700 | 5,7 | 4 821 | 16,69 |

| XVIII | Themisto | 7 507 000 | 21,0 | 9 | 130,0 |

| XIII | Leda | 11 165 000 | 20,2 | 18 | 240,9 |

| VI | Himalia | 11 461 000 | 14,8 | 160 | 250,6 |

| LXXI | Ersa | 11 483 000 | 22,9 | 3 | 252,0 |

| S/2018 J 2 | 11 490 000 | 23,3 | 3 | 252,0 | |

| LXV | Pandia | 11 525 000 | 23,0 | 3 | 252,1 |

| X | Lysithea | 11 717 000 | 18,1 | 38 | 259,2 |

| VII | Elara | 11 741 000 | 16,6 | 78 | 259,6 |

| S/2011 J 3 | 11 829 000 | 23,1 | 3 | 263,0 | |

| LIII | Dia | 12 118 000 | 22,4 | 4 | 287,0 |

| S/2018 J 4 | 16 548 600 | 23,5 | 2 | 434,7 | |

| XLVI | Carpo | 16 989 000 | 23,0 | 3 | 456,1 |

| LXII | Valetudo | 18 980 000 | 24,0 | 1 | 533,3 |

| XXXIV | Euporie | 19 302 000 | 23,1 | 2 | 550,7 |

| LV | S/2003 J 18 | 20 274 000 | 23,4 | 2 | 588,0 |

| LII | S/2010 J 2 | 20 307 150 | 23,9 | 1 | 588,1 |

| S/2003 J 16 | 20 567 000 | 23,3 | 2 | 598,6 | |

| S/2003 J 2 | 20 610 000 | 23,7 | 2 | 602,3 | |

| LXVIII | S/2017 J 7 | 20 627 000 | 23,6 | 2 | 602,6 |

| LIV | S/2016 J 1 | 20 650 845 | 24,0 | 1 | 602,7 |

| LXIV | S/2017 J 3 | 20 694 000 | 23,4 | 2 | 606,3 |

| XXXV | Orthosie | 20 721 000 | 23,1 | 2 | 622,6 |

| S/2021 J 1 | 20 723 000 | 23,9 | 1 | 606,4 | |

| XXXIII | Euanthe | 20 799 000 | 22,8 | 3 | 620,6 |

| XXIX | Thyone | 20 940 000 | 22,3 | 4 | 627,3 |

| S/2022 J 3 | 20 968 000 | 24,0 | 1 | 617,3 | |

| XL | Mneme | 21 069 000 | 23,3 | 2 | 620,0 |

| XXII | Harpalyke | 21 105 000 | 22,2 | 4 | 623,3 |

| XXX | Hermippe | 21 131 000 | 22,1 | 4 | 633,9 |

| XXVII | Praxidike | 21 147 000 | 21,2 | 7 | 625,3 |

| XLII | Thelxinoe | 21 162 000 | 23,5 | 2 | 628,1 |

| S/2021 J 2 | 21 197 500 | 24,0 | 1 | 627,8 | |

| LX | Eupheme | 21 199 710 | 23,4 | 2 | 627,8 |

| XLV | Helike | 21 263 000 | 22,6 | 4 | 634,8 |

| XXIV | Iocaste | 21 269 000 | 21,8 | 5 | 631,5 |

| XII | Ananke | 21 276 000 | 18,9 | 28 | 610,5 |

| LXX | S/2017 J 9 | 21 487 000 | 22,8 | 3 | 639,2 |

| S/2021 J 3 | 21 553 000 | 23,8 | 2 | 642,8 | |

| S/2003 J 12 | 21 615 000 | 24,0 | 1 | 646,0 | |

| S/2022 J 1 | 22 074000 | 23,8 | 2 | 668,4 | |

| S/2003 J 4 | 22 110 000 | 23,5 | 2 | 668,0 | |

| S/2016 J 3 | 22 273 000 | 23,6 | 2 | 675,7 | |

| LXVII | S/2017 J 6 | 22 455 000 | 23,5 | 2 | 683,0 |

| LXXII | S/2011 J 1 | 22 462 000 | 23,7 | 2 | 686,6 |

| S/2022 J 2 | 22 473 000 | 24,0 | 1 | 686,7 | |

| LXI | S/2003 J 19 | 22 757 000 | 23,7 | 2 | 697,6 |

| LVIII | Philophrosyne | 22 819 950 | 23,5 | 2 | 701,3 |

| XXXII | Eurydome | 22 865 000 | 22,7 | 3 | 717,3 |

| S/2018 J 3 | 22 888 000 | 23,9 | 1 | 704,9 | |

| S/2021 J 5 | 22 893 100 | 23,6 | 2 | 704,9 | |

| S/2003 J 10 | 22 918 300 | 23,8 | 2 | 704,9 | |

| XLIII | Arche | 22 931 000 | 22,8 | 3 | 723,9 |

| S/2021 J 4 | 22 950 000 | 24,0 | 1 | 708,6 | |

| XXVIII | Autonoe | 23 039 000 | 22,0 | 4 | 762,7 |

| XXXVIII | Pasithee | 23 096 000 | 23,2 | 2 | 719,5 |

| L | Herse | 23 097 000 | 23,4 | 2 | 715,4 |

| S/2003 J 24 | 23 150 000 | 23,8 | 2 | 715,9 | |

| XXI | Chaldene | 23 179 000 | 22,5 | 4 | 723,8 |

| XXXVII | Kale | 23 217 000 | 23,0 | 2 | 729,5 |

| XXVI | Isonoe | 23 217 000 | 22,5 | 4 | 725,5 |

| XXXI | Aitne | 23 231 000 | 22,7 | 3 | 730,2 |

| LXVI | S/2017 J 5 | 23 232 000 | 23,5 | 2 | 719,5 |

| LXIX | S/2017 J 8 | 23 232 700 | 24,0 | 1 | 719,6 |

| XXV | Erinome | 23 279 000 | 22,8 | 3 | 728,3 |

| LXIII | S/2017 J 2 | 23 303 000 | 23,5 | 2 | 723,1 |

| LI | S/2010 J 1 | 23 314 335 | 23,3 | 2 | 723,2 |

| XX | Taygete | 23 360 000 | 21,9 | 5 | 732,2 |

| XI | Carme | 23 404 000 | 17,9 | 46 | 702,3 |

| LVI | S/2011 J 2 | 23 463 885 | 23,6 | 1 | 730,5 |

| XXXVI | Sponde | 23 487 000 | 23,0 | 2 | 748,3 |

| S/2021 J 6 | 23 490 000 | 23,9 | 1 | 734,1 | |

| LIX | S/2017 J 1 | 23 547 105 | 23,8 | 2 | 734,2 |

| XXIII | Kalyke | 23 583 000 | 21,8 | 5 | 743,0 |

| VIII | Pasiphae | 23 624 000 | 16,9 | 58 | 708,0 |

| XLVII | Eukelade | 23 661 000 | 22,6 | 4 | 746,4 |

| S/2016 J 4 | 23 728 000 | 24,0 | 1 | 743,7 | |

| LVII | Eirene | 23 731 770 | 22,5 | 4 | 759,7 |

| XIX | Megaclite | 23 806 000 | 21,7 | 6 | 752,8 |

| IX | Sinope | 23 939 000 | 18,3 | 38 | 724,5 |

| XXXIX | Hegemone | 23 947 000 | 22,8 | 3 | 739,6 |

| XLI | Aoede | 23 981 000 | 22,5 | 4 | 761,5 |

| XLIV | Kallichore | 24 043 000 | 23,7 | 2 | 764,7 |

| XVII | Callirrhoe | 24 102 000 | 20,8 | 7 | 758,8 |

| S/2003 J 9 | 24 233 625 | 23,7 | 1 | 766,5 | |

| XLVIII | Cyllene | 24 349 000 | 23,2 | 2 | 737,8 |

| XLIX | Kore | 24 543 000 | 23,6 | 2 | 779,2 |

| S/2003 J 23 | 24 750 000 | 23,9 | 2 | 759,7 |

Referenser

- Marazzini, C., "The names of the satellites of Jupiter: from Galileo to Simon Marius". Lettere Italiane (in Italian) (2005) 57 (3), sid. 391–407.

- Galilei, Galileo – översatt av Albert Van Helden (1989), “Sidereus Nuncius”, Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, sid. 14–16. ISBN 0-226-27903-0.

Noter

- ^ [a b c d e] Sheppard, Scott S.. ”Moons of Jupiter”. Earth & Planets Laboratory. Carnegie Institution for Science. https://sites.google.com/carnegiescience.edu/sheppard/moons/jupitermoons. Läst 3 januari 2024.

- ^ ”Moons of Jupiter”. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/jupiter/moons/. Läst 3 januari 2024. ”Jupiter has 95 moons that have been officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union.”

- ^ Anderson, J.D.; Johnson, T.V.; Shubert, G. med flera (2005). ”Amalthea's Density Is Less Than That of Water”. Science (The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society) 308 (5726): sid. 1291–1293. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15919987.

- ^ Canup, Robert M.; Ward, William R. (2009). Origin of Europa and the Galilean Satellites. University of Arizona Press. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008arXiv0812.4995C

- ^ Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007). ”Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System”. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 45 (1): sid. 261–295. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459?journalCode=astro.

Se även

- Mars naturliga satelliter

- Saturnus naturliga satelliter

- Uranus naturliga satelliter

- Neptunus naturliga satelliter

Externa länkar

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Jupiters naturliga satelliter.

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Jupiters naturliga satelliter.

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Media som används på denna webbplats

Major Solar System objects. Sizes of planets and Sun are roughly to scale, but distances are not. This is not a diagram of all known moons – small gas giants' moons and Pluto's S/2011 P 1 moon are not shown.

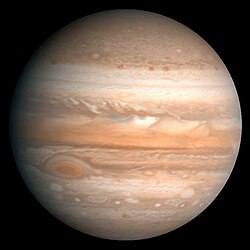

Original Caption Released with Image: This processed color image of Jupiter was produced in 1990 by the U.S. Geological Survey from a Voyager 2 image captured in 1979. The colors have been enhanced to bring out detail. Zones of light-colored, ascending clouds alternate with bands of dark, descending clouds. The clouds travel around the planet in alternating eastward and westward belts at speeds of up to 540 kilometers per hour. Tremendous storms as big as Earthly continents surge around the planet. The Great Red Spot (oval shape toward the lower-left) is an enormous anticyclonic storm that drifts along its belt, eventually circling the entire planet.

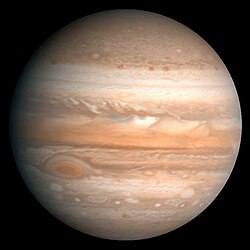

This composite includes the four largest moons of Jupiter which are known as the Galilean satellites. The Galilean satellites were first seen by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610. Shown from left to right in order of increasing distance from Jupiter, Io is closest, followed by Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

The order of these satellites from the planet Jupiter helps to explain some of the visible differences among the moons. Io is subject to the strongest tidal stresses from the massive planet. These stresses generate internal heating which is released at the surface and makes Io the most volcanically active body in our solar system. Europa appears to be strongly differentiated with a rock/iron core, an ice layer at its surface, and the potential for local or global zones of water between these layers. Tectonic resurfacing brightens terrain on the less active and partially differentiated moon Ganymede. Callisto, furthest from Jupiter, appears heavily cratered at low resolutions and shows no evidence of internal activity.

North is to the top of this composite picture in which these satellites have all been scaled to a common factor of 10 kilometers (6 miles) per picture element.

The Solid State Imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft acquired the Io and Ganymede images in June 1996, the Europa images in September 1996, and the Callisto images in November 1997.

Launched in October 1989, the spacecraft's mission is to conduct detailed studies of the giant planet, its largest moons and the Jovian magnetic environment.