Io (måne)

- För andra betydelser, se IO.

| Io | |

| |

| Upptäckt[1] | |

|---|---|

| Upptäckare | Galileo Galilei |

| Upptäcktsdatum | 8 januari 1610 |

| Beteckningar | |

| Alternativnamn | Jupiter I |

| Uppkallad efter | Io |

| Omloppsbana | |

| Apoapsis | 423 400 km (0,002 830 AU) |

| Periapsis | 420 000 km (0,002 807 AU) |

| Banmedelradie | 421 700 km (0,002 819 AU) |

| Excentricitet | 0,0041 |

| Siderisk omloppstid | 1,769 137 786 d (152 853,504 7 s, 42,459 306 86 h) |

| Medelomloppshastighet | d (152 853,504 7 s, 42,459 306 86 h) |

| Inklination | 0,05° (till Jupiters ekvator) |

| Måne till | Jupiter |

| Fysikaliska data | |

| Dimensioner | 3 660,0 × 3 637,4 × 3 630,6 km[2] |

| Medelradie | 1 821,3 km (0,286 av Jordens)[2] |

| Area | 41 910 000 km2 (0,082 av Jorden) |

| Volym | 2,53 × 1010 km3 (0,023 av Jorden) |

| Massa | 8,9319 × 1022 kg (0,015 av Jorden) |

| Medeldensitet | 3,528 g/cm3 |

| Ytgravitation (ekvatorn) | 1,796 m/s2 (0,183 g) |

| Flykthastighet | 2,558 km/s |

| Rotationsperiod | Synkron |

| Albedo | 0,63 ± 0,02[3] |

| Yttemperatur | Min: 90 K Medel: 110 K Max: 130 K[4] |

Io är den tredje största av Jupiters månar. Den är den innersta av de fyra galileiska satelliterna, och med en diameter på 3642 kilometer är Io den fjärde största månen i solsystemet. Månen är döpt efter prästinnan Io i den grekiska mytologin.

På grund av resonans med Jupiter och de tre övriga galileiska månarna - Europa, Ganymedes och Callisto, skapas enorma tidvattenkrafter på Io. Detta skapar friktion inuti Io och driver geologisk aktivitet. Med över 400 vulkaner på sin yta är Io det mest geologiskt aktiva objektet i solsystemet.[5][6]

Ios yta

Kratrar och vulkanism

Ios yta är radikalt olik någon annan kropps yta i vårt solsystem. Det kom som en stor överraskning för forskarna vid Voyagers första besök. De hade förväntat sig att se nedslagskratrar och på så sätt räkna antalet kratrar per areaenhet för att uppskatta åldern av Ios yta. Men det finns bara få, om ens några, kratrar på Io. Ytan är alltså väldigt ung. Istället för nedslagskratrar hittade Voyager 1 hundratals vulkankratrar, varav några är aktiva. Foton av faktiska eruptioner med 300 km höga moln sändes tillbaka av båda Voyagersonderna och av rymdsonden Galileo. Galileo utforskade Io mer i detalj och visade genom mätningar att lavaströmmarna är betydligt varmare än på jorden och att de består av magnesium och järn. Analyser av Voyagers bilder ledde forskarna att tro att lavan som flyter på Ios yta mest bestod av olika föreningar av smält svavel. Men andra studier tyder på att de är för heta för att vara flytande svavel. En ny idé är att Ios lava består av smält silikatsten. Nyligen gjorda observationer med Hubbleteleskopet tyder på att materialet kan vara rikt på natrium. Det kan också vara varierande material på olika platser. Vissa av de hetaste punkterna på Io når temperaturer på 1 500 K, trots att medeltemperaturen är mycket lägre, ca 130 K. Dessa heta punkter är den huvudsakliga mekanismen vid vilken Io förlorar sin hetta.

Dessa observationer kan ha varit några av de viktigaste upptäckterna i Voyageruppdragen och i Galileo-projektet; det var det första verkliga beviset att andra "jordiska" kroppars inre faktiskt är hett och aktivt. Materialet som skjuts ut från Ios vulkaniska lufthål verkar vara någon form av svavel eller svaveldioxid. De vulkaniska eruptionerna ändras snabbt. På bara fyra månader mellan ankomsterna av Voyager 1 och Voyager 2 upphörde vissa av dem och nya startade. Avlagringarna som omgav lufthålen ändrades också synligt.

Bilder som nyligen tagits med NASAs infraröda teleskopanordningar på Mauna Kea på Hawaii visar en ny och väldigt stor eruption. En ny stor formation nära Ra Patera har också observerats av Rymdteleskopet Hubble. Bilder från Galileo visar också många förändringar från tiden av Voyagers besök. Dessa observationer bekräftar att Ios yta faktiskt är väldigt aktiv.

Energin för all denna aktivitet härleder antagligen från tidvattenkrafter mellan Io, Europa, Ganymedes och Jupiter. De tre satelliterna är låsta i omloppsbanor så att Io går runt två gånger för varje varv Europa gör, som i sin tur går runt två gånger för varje varv Ganymede gör. Trots att Io, precis som månen, alltid visar samma sida mot sin planet, får påverkan av Europa och Ganymedes den att rubbas lite. Denna rubbning sträcker och böjer Io så mycket som 100 m och genererar värme på samma sätt som en klädhängare värms upp när den böjs fram och tillbaka. Io korsar också Jupiters magnetfältslinjer vilket genererar en elektrisk ström. Trots att det är litet jämfört med tidvattensuppvärmningen, kan effekten bli mer än 1 triljon watt.

Nya data från Galileo tyder på att Io kan ha ett eget magnetfält, vilket Ganymedes har. Io har en tunn atmosfär bestående av svaveldioxid och kanske några andra gaser.

Till skillnad från de övriga galileiska satelliterna har Io bara lite, eller inget, vatten. Detta beror troligen på att Jupiter var tillräckligt het för att tidigt i evolutionen av vårt solsystem, driva bort flyktiga element i Ios omgivning men inte tillräckligt het för att göra det längre ut.

Se även

- Io, mytologisk gestalt.

Referenser

- ^ ”IAU Planetary Names”. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/Planets#JovianSystem. Läst 28 november 2011.

- ^ [a b] Thomas, P. C. (1998). ”The Shape of Io from Galileo Limb Measurements”. Icarus 135 (1): sid. 175–180. doi:.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K. (13 juli 2006). ”Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters”. JPL Solar System Dynamics. https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par. Läst 5 november 2007.

- ^ Rathbun, J. A.; Spencer, J.R.; Tamppari, L.K.; Martin, T.Z.; Barnard, L.; Travis, L.D. (2004). ”Mapping of Io's thermal radiation by the Galileo photopolarimeter-radiometer (PPR) instrument”. Icarus 169 (1): sid. 127–139. doi:.

- ^ Rosaly MC Lopes (2006). ”Io: The Volcanic Moon”. Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Academic Press. sid. 419–431. ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3

- ^ Lopes, R. M. C. (2004). ”Lava lakes on Io: Observations of Io’s volcanic activity from Galileo NIMS during the 2001 fly-bys”. Icarus 169 (1): sid. 140–174. doi:.

Externa länkar

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Io.

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Io.

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Media som används på denna webbplats

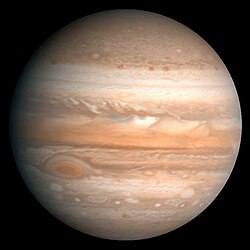

Original Caption Released with Image:

NASA's Galileo spacecraft acquired its highest resolution images of Jupiter's moon Io on 3 July 1999 during its closest pass to Io since orbit insertion in late 1995. This color mosaic uses the near-infrared, green and violet filters (slightly more than the visible range) of the spacecraft's camera and approximates what the human eye would see. Most of Io's surface has pastel colors, punctuated by black, brown, green, orange, and red units near the active volcanic centers. A false color version of the mosaic has been created to enhance the contrast of the color variations.

The improved resolution reveals small-scale color units which had not been recognized previously and which suggest that the lavas and sulfurous deposits are composed of complex mixtures (Cutout A of false color image). Some of the bright (whitish), high-latitude (near the top and bottom) deposits have an ethereal quality like a transparent covering of frost (Cutout B of false color image). Bright red areas were seen previously only as diffuse deposits. However, they are now seen to exist as both diffuse deposits and sharp linear features like fissures (Cutout C of false color image). Some volcanic centers have bright and colorful flows, perhaps due to flows of sulfur rather than silicate lava (Cutout D of false color image). In this region bright, white material can also be seen to emanate from linear rifts and cliffs.

Comparison of this image to previous Galileo images reveals many changes due to the ongoing volcanic activity.

Galileo will make two close passes of Io beginning in October of this year. Most of the high-resolution targets for these flybys are seen on the hemisphere shown here.

North is to the top of the picture and the sun illuminates the surface from almost directly behind the spacecraft. This illumination geometry is good for imaging color variations, but poor for imaging topographic shading. However, some topographic shading can be seen here due to the combination of relatively high resolution (1.3 kilometers or 0.8 miles per picture element) and the rugged topography over parts of Io. The image is centered at 0.3 degrees north latitude and 137.5 degrees west longitude. The resolution is 1.3 kilometers (0.8 miles) per picture element. The images were taken on 3 July 1999 at a range of about 130,000 kilometers (81,000 miles) by the Solid State Imaging (SSI) system on NASA's Galileo spacecraft during its twenty-first orbit.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA manages the Galileo mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, DC.

This image and other images and data received from Galileo are posted on the World Wide Web, on the Galileo mission home page at URL http://galileo.jpl.nasa.gov. Background information and educational context for the images can be found at URL http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/galileo/sepo.Original Caption Released with Image: This processed color image of Jupiter was produced in 1990 by the U.S. Geological Survey from a Voyager 2 image captured in 1979. The colors have been enhanced to bring out detail. Zones of light-colored, ascending clouds alternate with bands of dark, descending clouds. The clouds travel around the planet in alternating eastward and westward belts at speeds of up to 540 kilometers per hour. Tremendous storms as big as Earthly continents surge around the planet. The Great Red Spot (oval shape toward the lower-left) is an enormous anticyclonic storm that drifts along its belt, eventually circling the entire planet.

This composite includes the four largest moons of Jupiter which are known as the Galilean satellites. The Galilean satellites were first seen by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610. Shown from left to right in order of increasing distance from Jupiter, Io is closest, followed by Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

The order of these satellites from the planet Jupiter helps to explain some of the visible differences among the moons. Io is subject to the strongest tidal stresses from the massive planet. These stresses generate internal heating which is released at the surface and makes Io the most volcanically active body in our solar system. Europa appears to be strongly differentiated with a rock/iron core, an ice layer at its surface, and the potential for local or global zones of water between these layers. Tectonic resurfacing brightens terrain on the less active and partially differentiated moon Ganymede. Callisto, furthest from Jupiter, appears heavily cratered at low resolutions and shows no evidence of internal activity.

North is to the top of this composite picture in which these satellites have all been scaled to a common factor of 10 kilometers (6 miles) per picture element.

The Solid State Imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft acquired the Io and Ganymede images in June 1996, the Europa images in September 1996, and the Callisto images in November 1997.

Launched in October 1989, the spacecraft's mission is to conduct detailed studies of the giant planet, its largest moons and the Jovian magnetic environment.Cutaway view of the possible internal structure of Io The surface of the satellite is a mosaic of images obtained in 1979 by NASA's Voyager spacecraft The interior characteristics are inferred from gravity field and magnetic field measurements by NASA's Galileo spacecraft. Io's radius is 1821 km, similar to the 1738 km radius of our Moon; Io has a metallic (iron, nickel) core (shown in gray) drawn to the correct relative size. The core is surrounded by a rock shell (shown in brown). Io's rock or silicate shell extends to the surface.