Höftled

Höftled (latin: articulatio coxa) är i människans anatomi en synovial kulled mellan lårbenshuvudet (caput femoris) och höftledsgropen (acetabulum). Leden utgör axialskelettets och bäckengördelns övergång i lårbenet (os femoris) och ben. Med höften avses själva höftleden och de mjuka vävnaderna som omger den. I dagligt tal syftar dock ordet höften ofta på höftbenskammen.

I leden medges flexion på 0–160°, extension på 0–30°, abduktion på 0–45°, adduktion på 0–30°, utåtrotation 0–60° och inåtrotation på 0–40°.

Höftleden utsätts för stora belastningar och är därför mycket stark, stabil och tät. Höftledsgropen är mycket djup och lårbenshuvudet sitter djupt in i bäckenet (pelvis). Dessutom förstärks ledhålan av en omgivande ledläpp som i praktiken fördjupar leden. Leden omges av kraftiga ligament och skelettmuskler vilket förstärker den ossöa stabiliteten. En fettkudde, pulvinar acetabuli, fungerar som stötdämpare i leden.

Höftledens mekanik påverkas av den långa lårbenshalsen (collum ossis femoris) som riktar ledkulan framåt, uppåt och medialt. Ledbrosket är som starkast precis där trycköverföringen sker vid gång.

Ligament

- Lig. ischiofemorale

- Lig. iliofemorale

- Lig. pubofemorale

Muskler

De muskler som påverkar rörelserna i höftleden kan delas in i fyra muskelgrupper efter sin orientering kring leden.

Bildning och ossifikation

Fram till omkring 25-årsåldern består fortfarande höftbenet (os coxae) av tre separata ben: Tarmbenet (os ilium), sittbenet (os ischii) och blygdbenet (os pubis). Benbildningen av leden är alltså inte klar förrän barndomen är avslutad.

Referenser

- Motsvarande engelskspråkiga artikel den 24 september 2006

- Gray's Anatomy - Coxal Articulation or Hip-joint (Articulatio Coxæ).

- Rörelseapparatens anatomi, Finn Bojsen-Møller, Liber, ISBN 91-47-04884-0

Se även

Externa länkar

Media som används på denna webbplats

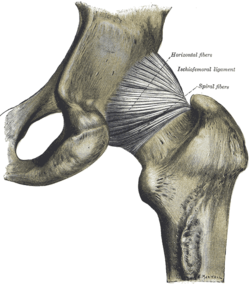

The hip-joint from behind. (Quain.)

Författare/Upphovsman: Ingen maskinläsbar skapare angavs. Scuba-limp~commonswiki antaget (baserat på upphovsrättsanspråk)., Licens: CC-BY-SA-3.0

Normal hip-joint

Författare/Upphovsman: Beth ohara, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

Anterior Hip Muscles

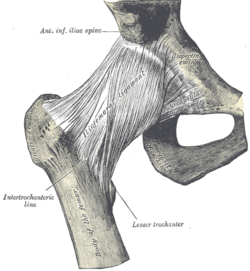

Right hip-joint from the front. (Spalteholz.)

An A-P X-ray of a pelvis showing a total hip joint replacement. The right hip joint (on the left in the photograph) has been replaced. A metal prostheses is cemented in the top of the right femur and the head of the femur has been replaced by the rounded head of the prosthesis. A white plastic cup is cemented into the acetabulum to complete the two surfaces of the artificial "ball and socket" joint.

Although not the case here, hip prostheses can also be made of a ceramic material which rarely wears out during the patient's lifetime. During the operation, a bonding cement is used to fix the metal prostheses into the shaft of the femur and the plastic cup to the acetabulum (socket in the hip bone). One of the leading reasons for hip replacement is osteoarthritis of the hip joint in which virtually all of the cartilage around the top of the femur bone deteriorates due to wear over time, leaving a grinding bone-on-bone situation with the bone surfaces becoming roughened leading to pain and stiffness. Narrowing of joint space (the space between the acetabulum and the head of the femur) is also a feature of osteoarthritis. There may be other changes which are not entirely clear on this A-P X-ray, which probably should be reported together with lateral X-rays of the hips, or with modern computerised imaging techniques.

Keywords: total hip replacement, prosthesis, osteoarthritis, X-ray.Författare/Upphovsman: Beth ohara~commonswiki, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

Posterior view of gluteal region showing the small gluteal muscles and gluteus minimus.

![Höger höftled framifrån. (Spalteolz)[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f1/Gray339.png/138px-Gray339.png)

![Höftleden bakifrån. (Quain)[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Gray340.png/132px-Gray340.png)