Callisto

| Callisto (måne) | |

| |

| Upptäckt[1] | |

|---|---|

| Upptäckare | Galileo Galilei |

| Upptäcktsdatum | 7 januari 1610 |

| Beteckningar | |

| Alternativnamn | Jupiter IV |

| Uppkallad efter | Kallisto |

| Omloppsbana[2] | |

| Halv storaxel | 1 882 700 km |

| Excentricitet | 0,0074 |

| Siderisk omloppstid | 16,69 dagar |

| Medelomloppshastighet | 29 531,6 km/h[3] |

| Medelanomali | 181,408° |

| Inklination | 0,192° |

| Longitud för uppstigande nod | 298,848° |

| Medelrörelse | 21,5710728°/dag |

| Måne till | Jupiter |

| Propra banelement | |

| Periheliumprecession | 205,75 år |

| Precession för uppstigande nod | 338,82 år |

| Fysikaliska data | |

| Medelradie | 2410,3±1,5 km[4] |

| Ekvatorradie | 2410,3 km[3] |

| Omkrets | 15 144,4 km[3] |

| Area | 73 004 909,27 km²[3] |

| Volym | 58 654 577 603 km³[3] |

| Massa | 1,0759 × 1023 kg[3] |

| Medeldensitet | 1,834±0,004 g/cm³[4] |

| Ytgravitation (ekvatorn) | 1,236 m/s²[3] |

| Flykthastighet | 2441 m/s[3] |

| GM | 7179,289±0,013 km³/s²[4] |

| Albedo | 0,17±0,02[4] |

| Skenbar magnitud | 5,65±0,10[4] |

| Atmosfär[3] | |

| Sammansättning | koldioxid |

Callisto är den åttonde av Jupiters kända månar och den näst största, endast något mindre än Merkurius men bara en tredjedel av dess massa. Den upptäcktes av Galileo Galilei och Simon Marius den 7 januari 1610 och är den yttersta av de galileiska månarna.[1]

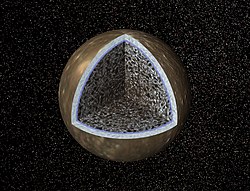

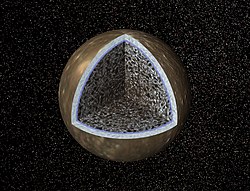

Till skillnad från Ganymedes verkar Callisto ha ganska lite inre struktur. Callisto studerades i detalj av rymdsonden Galileo mellan åren 1995 och 2003. Mätningar som sonden gjorde visade att de inre delarna av månen har en ökande halt sten mot kärnan. Callisto består av ungefär 40 % is och 60 % sten och järn. Titan och Triton är antagligen liknande.

Callistos yta är helt täckt av kratrar. Ytan är väldigt gammal, precis som högländerna på månen och Mars. Callisto har den äldsta och mest bekratrade ytan av alla kroppar som hittills observerats i solsystemet. Den har inte genomgått mycket mer förändring än ett och annat nedslag under 4 miljarder år.

De största kratrarna omges av en serie koncentriska ringar som ser ut som enorma sprickor men som har jämnats ut av eoner av långsam rörelse av isen. Den största av dessa kratrar är Valhalla. Med sina 4000 kilometer i diameter är Valhalla ett dramatiskt exempel på en multiringkrater, resultatet av ett massivt nedslag. Den näst största är Asgard. Andra exempel i solsystemet är Mare Orientale på månen och Caloris Basin på Merkurius.

Liksom Ganymedes har Callistos forntida kratrar kollapsat, de höga ringbergen och de centrala sänkorna vanliga hos kratrarna på månen och Merkurius saknas. Detaljerade bilder från rymdsonden Galileo visar att små kratrar, åtminstone på vissa ställen, för det mesta har utplånats. Detta tyder på nyliga processer även om det bara är en gissning.

Gipul Catena är en lång serie av nedslagskratrar uppradade på en rak linje. Detta orsakades antagligen av ett objekt som splittrades när den passerade nära Jupiter och sedan slog ner på Callisto.

Till skillnad från Ganymedes, med sina komplexa terränger, finns det knappast något som tyder på tektonisk aktivitet på Callisto. Rymdsonden Galileo har inte upptäckt några bevis för ett magnetfält.

Utforskning

När de båda rymdsonderna Pioneer 10 och Pioneer 11 passerade Jupiter, kunde de inte bidra med mer information om Callisto än man kunnat utröna med observationer från Jorden.[5][6]

När de båda rymdsonderna Voyager 1 och Voyager 2 passerade Jupiter, fotograferade dom stora delar av Callisto, flera foton har en upplösning på 1-2 kilometer.[7]

Rymdsonden Galileo passerade Callisto flera gånger mellan 1994 och 2003 och kunde göra en komplett karta av månen yta, flera foton har en upplösning på 15 meter. Rymdsonden kom som närmast 138 kilometer från Callistos yta.[8]

Rymdsonden Cassini passerade Jupiter i december 2000 och studerade den Callisto i infrarötljus.[9]

Även rymdsonden New Horizons fotograferade Callisto, när den passerade Jupiter i februari 2007.[10]

Rymdsonderna Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer och Europa Clipper är påväg mot Jupiter och kommer bland annat studera Callisto.[11]

Källor

- ^ [a b] ”Callisto: In Depth” (på engelska). NASA. https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/callisto/indepth. Läst 17 augusti 2016.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory. ”Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters” (på engelska). Solar System Dynamics. NASA. https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_elem. Läst 17 augusti 2016.

- ^ [a b c d e f g h i] ”Callisto: By the Numbers” (på engelska). NASA. https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/callisto/facts. Läst 17 augusti 2016.

- ^ [a b c d e] Jet Propulsion Laboratory. ”Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters” (på engelska). Solar System Dynamics. NASA. https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par. Läst 17 augusti 2016.

- ^ ”Pioneer 10” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/pioneer-10/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

- ^ ”Pioneer 11” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/pioneer-11/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

- ^ ”Voyager” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/voyager/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

- ^ ”Galileo” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/galileo/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

- ^ ”Cassini” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

- ^ ”New Horizons” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/new-horizons/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

- ^ ”Europa Clipper” (på engelska). NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/europa-clipper/. Läst 9 mars 2025.

Externa länkar

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Callisto.

Wikimedia Commons har media som rör Callisto.

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Media som används på denna webbplats

- Textured Terrain in Callisto's Asgard Basin

- original image caption: This fascinating region of Jupiter's icy moon, Callisto, shows the transition from the inner part of an enormous impact basin, Asgard, to the outer "surrounding plains." Small, bright, fine textured, closely spaced bumps appear throughout the inner part of the basin (top of image) and create a more fine textured appearance than that seen on many of the other inter-crater plains on Callisto. At low resolution, these icy bumps make Asgard's center brighter than the surrounding terrain. What caused the bumps to form is still unknown, but they are associated clearly with the impact that formed Asgard. The ridge that cuts diagonally across the lower left corner is one of many giant concentric rings that extend for hundreds of kilometers outside Asgard's center. Exterior to the ring (lower left corner), Callisto's surface changes significantly. Still peppered with craters, the number of icy bumps decreases while their average size increases. The fine texture is not as visible in the middle of the image. One explanation is that material from raised features (such as the ridge) may slide down slope and cover small scale features. Such images of Callisto help us understand the dynamics of giant impacts into icy surfaces, and how the large structures change with time. North is to the top of the picture. The image, centered at 27.1 degrees north latitude and 142.3 degrees west longitude, covers an area approximately 80 kilometers (50 miles) by 90 kilometers (55 miles). The resolution is about 90 meters (295 feet) per picture element. The image was taken on September 17th, 1997 at a range of 9200 kilometers (5700 miles) by the Solid State Imaging (SSI) system on NASA's Galileo spacecraft during its tenth orbit of Jupiter.

Bright scars on a darker surface testify to a long history of impacts on Jupiter's moon Callisto in this image of Callisto from NASA's Galileo spacecraft. The picture, taken in May 2001, is the only complete global color image of Callisto obtained by Galileo, which has been orbiting Jupiter since December 1995. Of Jupiter's four largest moons, Callisto orbits farthest from the giant planet. Callisto's surface is uniformly cratered but is not uniform in color or brightness. Scientists believe the brighter areas are mainly ice and the darker areas are highly eroded, ice-poor material.

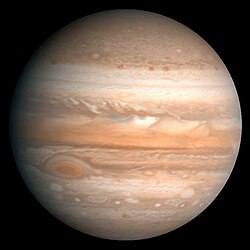

Original Caption Released with Image: This processed color image of Jupiter was produced in 1990 by the U.S. Geological Survey from a Voyager 2 image captured in 1979. The colors have been enhanced to bring out detail. Zones of light-colored, ascending clouds alternate with bands of dark, descending clouds. The clouds travel around the planet in alternating eastward and westward belts at speeds of up to 540 kilometers per hour. Tremendous storms as big as Earthly continents surge around the planet. The Great Red Spot (oval shape toward the lower-left) is an enormous anticyclonic storm that drifts along its belt, eventually circling the entire planet.

This composite includes the four largest moons of Jupiter which are known as the Galilean satellites. The Galilean satellites were first seen by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610. Shown from left to right in order of increasing distance from Jupiter, Io is closest, followed by Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

The order of these satellites from the planet Jupiter helps to explain some of the visible differences among the moons. Io is subject to the strongest tidal stresses from the massive planet. These stresses generate internal heating which is released at the surface and makes Io the most volcanically active body in our solar system. Europa appears to be strongly differentiated with a rock/iron core, an ice layer at its surface, and the potential for local or global zones of water between these layers. Tectonic resurfacing brightens terrain on the less active and partially differentiated moon Ganymede. Callisto, furthest from Jupiter, appears heavily cratered at low resolutions and shows no evidence of internal activity.

North is to the top of this composite picture in which these satellites have all been scaled to a common factor of 10 kilometers (6 miles) per picture element.

The Solid State Imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft acquired the Io and Ganymede images in June 1996, the Europa images in September 1996, and the Callisto images in November 1997.

Launched in October 1989, the spacecraft's mission is to conduct detailed studies of the giant planet, its largest moons and the Jovian magnetic environment.This artist's concept, a cutaway view of Jupiter's moon Callisto, is based on recent data from NASA's Galileo spacecraft which indicates a salty ocean may lie beneath Callisto's icy crust.

These findings come as a surprise, since scientists previously believed that Callisto was relatively inactive. If Callisto has an ocean, that would make it more like another Jovian moon, Europa, which has yielded numerous hints of a subsurface ocean. Despite the tantalizing suggestion that there is an ocean layer on Callisto, the possibility that there is life in the ocean remains remote.

Callisto's cratered surface lies at the top of an ice layer, (depicted here as a whitish band), which is estimated to be about 200 kilometers (124 miles) thick. Immediately beneath the ice, the thinner blue band represents the possible ocean, whose depth must exceed 10 kilometers (6 miles), according to scientists studying data from Galileo's magnetometer. The mottled interior is composed of rock and ice.

Galileo's magnetometer, which studies magnetic fields around Jupiter and its moons, revealed that Callisto's magnetic field is variable. This may be caused by varying electrical currents flowing near Callisto's surface, in response to changes in the background magnetic field as Jupiter rotates. By studying the data, scientists have determined that the most likely place for the currents to flow would be a layer of melted ice with a high salt content.

These findings were based on information gathered during Galileo's flybys of Callisto in November 1996, and June and September of 1997. JPL manages the Galileo mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, DC.